La Selva continues as a key site for research on bats, highlighting the complexity and diversity of bat ecology. Carollia perspicilliata is a frugivorous bat that functions as an important disperser of seeds of Piper and other pioneer plants throughout the Central and South American tropics. In feeding on Piper, bats encounter nutrients but also secondary plant compounds, thought to function in plant defense. However, these compounds may have toxic properties that influence how frugivores feed and digest the fruit. Gelambi et al. (2024)[4] investigated how Carollia foraging behavior and the ability to acquire nutrients may be affected by the chemical piperine. Piperine is present in abundant but of variable concentration in Piper fruits. Although piperine reduced protein absorption for the bats, captive bats tested with artificial diets preferred food with high nutrient content, even if it contained high levels of piperine. The authors suggested that these results highlight the importance of considering multiple chemical traits to understand frugivore foraging behavior. In a different study on two co-existing nectar-feeding bats, Bechler et al. (2024)[5] found that not only do specialist and generalist feeders differ in the types of flowers visited as predicted, the feeding efficiency of the two types of bats did not differ between flower species with abundant nectar, but did differ on a flower species that is has little flower available per individual flower.

OTS is represented in large-scale and comparative studies. Two recent papers highlight the importance of cross-comparisons and make use of data from La Selva as well as other sites in the Neotropics. Massad et al. 2024[6] examined patterns of herbivory on species of Piper across Neotropical forests. The authors integrated multiple factors that might influence the magnitude of herbivory, focusing on what they term “biologically meaningful” herbivory, that is, relatively high amounts of herbivory expected to affect aspects such as plant survival, reproduction, or carbon acquisition. Herbivory was nearly doubled in humid compared to seasonal forests. Abiotic factors as well as the local species richness of Piper were important in explaining large amounts of herbivory.

In a new paper, Sun et al.(2024)[7] assessed cover and diversity of broad-leaved monocot herbs communities in a chronosequence of 1 ha permanent plots established as part of the BOSQUES project on tropical forest regeneration, including plots at La Selva and throughout the surrounding landscape. Among other results, the authors found that species richness increased along the chronosequence, with the highest number of species in primary forest. Over half of the species found showed some degree of clonal growth, although the extent of cloning differed among species and forest stands.

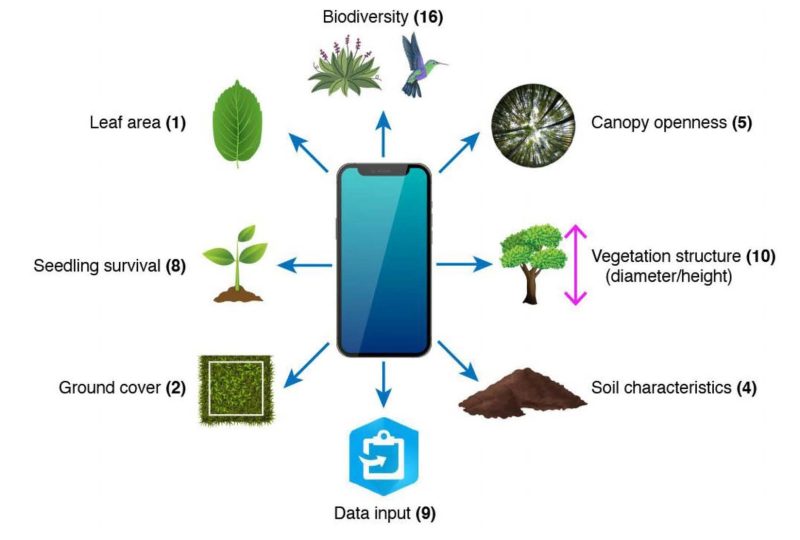

Long-term research at Las Cruces Research Station on forest restoration (ISLAS forest restoration project led by researchers Zahawi, Holl, and Cole) was featured in a recent review of smartphone apps for forest restoration monitoring[8]. Five apps were compared to traditional field techniques. The apps compared favorably to traditional techniques in terms of cost and tree diameter measurements but did not correlate well with other standard measurements of forest structure taken with traditional methods. The authors recommended that smartphone apps need further development and validation, and could be used in concert with a comprehensive data repository on forest restoration.

[1] Osorto Nuñez et al.2024. Revista de Biologia Tropical 72(1), e53238. doi.org/10.15517/rev.biol.trop., v72i1.53238

[2] Schrier et al. 2023. Primate Conservation 37: 35-44. http://www.primate-sg.org/storage/pdf/PC37_Schreier_et_al_A_palliata_demographics.pdf

[3] Ehrie et al. 2024. Am. J. Primatol. 2024; 86(6), e23616. doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23616

[4] Gelambi et al. 2024. Ecosphere. 2024;15:e4843. doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.4843

[5] Bechler et al. 2024. PLOS ONE. 19(6): e0303227. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303227

[6] Massad et al. 2023. Oikos 2024(2): e10218. doi.org/10.1111/oik.10218

[7] Sun et al.(2024) Diversity 2024, 16, 439. doi.org/10.3390/d16080439

[8] Schweizer et al. 2024. Restoration Ecology Vol. 32, No. 4, e14136