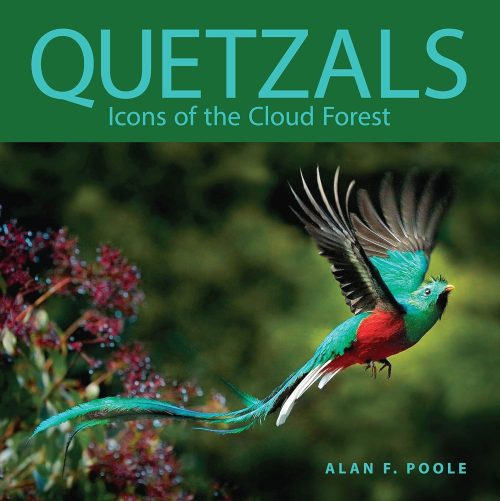

Quetzals: Icons of the Cloud Forest

Alan F. Poole

The following is an excerpt from Alan F. Poole’s book, Quetzals: Icons of the Cloud Forest:

“……a bird of such incredible beauty that for 200 years European naturalists thought it must be the fabrication of American aboriginies. A bird so sacred to the ancient Maya that to kill one was a capital crime. A bird so closely associated with its lofty home in the Central American cloud forest that as the forests vanished, so too did the bird. A bird that has been a symbol of liberty for several thousand years — not the shrill, defiant liberty of the eagle, but the serene and innocent liberty of the child at play.” J. E. Maslow on the Resplendent Quetzal; from Bird of Life, Bird of Death. 1986.

“The male is a supremely lovely bird; the most beautiful, all things considered, that I have ever seen. He owes his beauty to the intensity and arresting contrast of his coloration, the resplendent sheen and glitter of his plumage, the elegance of his ornamentation, the symmetry of his form, and the noble dignity of his carriage.” Alexander Skutch, Life History of the Quetzal, 1944.

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

It was the feather that first caught my attention. An emerald green feather, long and supple, protruding from a hole in a decaying tree trunk, waving gently in the faint morning breeze. As a budding young birdwatcher, new to the American tropics and lucky enough to be wandering a cloud forest trail in Costa Rica, I thought I was ready for anything. But not this, not such an improbable sight — a tree sprouting feathers. Suddenly that feather disappeared, swept into the hole in a flash, and a head poked out to replace it. And what a head! Topped by a golden-green, iridescent crest; fronted by a short, stout, powder-yellow beak; centered with a jet-black eye, focused intently on me; and surrounding that eye, cheek to jowl, a radiant circle of shining green feathers, a jade sunburst. These were feathers on a mission, feathers like I’d never seen before. Then and there I resolved to discover what that mission was.

Before I could blink, the full bird emerged, launching out from its hole and rocketing off into the forest, a shimmering blur of emerald and ruby, its long iridescent tail unspooling behind it like a ribbon, calling a mellow, haunting waca, waca, waca. Now that tree-trunk feather mystery was solved: it was a tail, I could see, a very long tail, maybe a meter or more from body to tip. Long enough to be still coming into a hole while the rest of the bird was heading out — like a caboose glimpsed from a locomotive when a train rounds a sharp bend in the tracks. Clearly this tail was not an everyday phenomenon, and this was not an everyday bird. Only one bird in Central America had a tail like that, I knew: I’d just seen my first Resplendent Quetzal!

And, I soon discovered, it wasn’t really a “tail” I had seen. Those long feathers streaming behind the male bird were its tail-coverts, four super-elongated feathers that grow out above the shorter, stabilizing tail feathers, the rectrices, and cover much of their dorsal surface (top). But to most observers, me included, it’s just a “tail” that you see as this quetzal dives into the forest.

Like first love, first encounters with quetzals can vary in untold ways. In my case I’d been lucky; so many quetzal elements had come together at the same time: a brilliant male Resplendent, at rest and in flight; a nest hole, glimpsed up close, with its hints of new life emerging from dead wood; and those haunting quetzal calls echoing on in my mind long after the bird had disappeared. Stunned, intrigued, my curiosity aroused, I knew this was a bird I had to seek out and spend more time with. And over the years, I am pleased to say, this has come to pass — many delightful hours in quetzal forests; many contemplative days in libraries, uncovering a trove of quetzal lore; and many hours in conversation with a host of different people, from tiny remote highland villages to prestigious urban scientific universities. All people united in quetzal admiration.

It didn’t take me long to discover a few key facts about Resplendent Quetzals: that they are one of five quetzal species in the genus Pharomachrus, all quintessentially American birds confined (except for one) to the highland cloud forests of Central and South America. That the Resplendent was the most northerly of the five, ranging from the mountains of Chiapas Mexico to those of northwestern Panama. That, like all highland quetzals, Resplendents live at tropical latitudes but (owing to elevation) in cool temperate climates, a land of drizzly mists, chilly and often windy nights, occasional brilliant days, and (in certain months) torrential rains. For humans who traverse these mountains, they are all too often a land of mud. Trudging through that mud, as you so often do in quetzal highlands, it can seem an anomaly that out of these dank and dreary landscapes have sprung some of the most brilliantly plumaged birds in the world.

I also discovered that to get to quetzals, to their beginnings, you have to start with their close relatives the trogons — a family of hole-nesting, fruit-eating, compact-bodied and brightly-plumaged tropical forest birds. Trogons have a global reach but achieve their highest diversity in the Americas. Thanks to DNA analysis, along with emerging details from geological research, it’s now clear that quetzals evolved from trogons at least three to six million years ago, as changing sea levels opened land bridges between North and South America, releasing trogons into rich new forests and jump-starting a proliferation of new species. One of these trogons likely emerged as a proto-quetzal, probably on the eastern slopes of the Andes, a bird no longer with us but some of whose genes continue on in the five Pharomachrus quetzals that grace our world today. In this slow shaping of trogons into quetzals we see where evolution has been nudging these birds — toward more elaborate plumage, a more fruit-centered diet, more social behavior, and a reliance on nest holes in dead, well-rotted trees. All this has brought us the quetzals we know today. In many ways they are trogons that evolution has taken to extremes, culminating in those gaudy male Resplendents with their extraordinary golden crests and meter-long “tails.” Central Americans speak of the Resplendent Quetzal as “El Rey de los Trogones” — the king of the trogons. It’s hard to think of a more fitting moniker.

Along with the Resplendent, four other Pharomachrus quetzals have found a home in America’s tropical forests: the Pavonine (P. pavoninus), a bird of hot and humid lowland Amazonia, the only lowland quetzal; the Golden-headed (P. auriceps), a cloud forest resident along both eastern and western slopes of South America’s Andes Mountains; the Crested (P. antisianus), which joins auriceps in those same wet and windy Andean highlands; and the White-tipped Quetzal (P. fulgidus), restricted to a narrow band of coastal mountain forest in the northern reaches of Colombia and Venezuela. All these will find a place in this book, but it is the Resplendent Quetzal that will be front and center, mostly because we know so much more about this bird than we do about the other Pharomachrus, which remain virtually unstudied. The spotlight is on Resplendents not just because they dazzle so brightly, but also because there is so little light for the others.

Resplendent Quetzals have captured people’s attention for millennia. Those same feathers that caught my eye in the highlands of Costa Rica in the 1980s caught other eyes starting at least 3,000 years ago. For the increasingly complex and developed human cultures of Mexico and Central America, especially the Mayans and Aztecs, those long tail coverts of male Resplendent Quetzals took on mythical and religious status, their jade-green color evoking rebirth. Their value to these people soared, surpassing that of gold, and a robust trade sprang up to supply kings, priests, and nobility, the only sectors of society permitted to wear the garments into which those precious feathers were woven. Interestingly, it was those covert feathers alone that had value; the bird itself was hardly known, hardly acknowledged in art and lore. And with good reason. Resplendents lived in mountains remote from Aztec and Mayan population centers, so other than wandering traders few, if any, of these people ever saw a live quetzal.

But the life of this quetzal, the real bird that the Aztecs barely knew, has its own magical allure. To understand why we have to go beyond the feathers, incredible as they are. And we’re helped in this quest by the nature of this bird. Although it can be elusive, hidden away in deep forest, the Resplendent Quetzal can also live quite compatibly alongside humans in more settled areas, where forests edge into field and pasture. In such a landscape mosaic they often turn out to be surprisingly tame and visible, gathering in small groups at pasture edges as cows graze beneath them, and even snatching fruits from backyard trees. As a result, this is a bird that people — including a small but devoted group of scientists — have gotten to know over time. A handful of studies, most in the past 4-5 decades, stand out in describing the life history of this quetzal, in making its story possible to tell.

We start with the legendary ornithologist, Alexander Skutch, who spent almost a year during the early 1940s, as World War II raged on in Europe, living alone in a cabin in the remote and peaceful highlands of Costa Rica, where Resplendent Quetzals nested abundantly in those years. Resplendents were his quest in those months. His detailed observations, focused on nesting pairs, provide the foundation for what we know about how these birds go about reproducing: that male and female parents share nesting duties pretty equally, unusual for male birds with such gaudy plumage; that the dead-tree nest holes they take over from woodpeckers need considerable retrofitting to accommodate quetzal eggs and young; that the diet of breeders centers on just a handful of trees in the family Lauraceae, trees that produce small, fat-rich fruits (miniature avocados, essentially) that power quetzal life in that wet, chilly climate; that a supplement of animal protein (insects, lizards, snails) is needed to fuel the growth of nestlings – fruit alone won’t do it; and that many pairs produce two broods each year, the second quickly following the first. In short, Skutch showed us a bird with a life that depends on a limited number of trees: at most a few dozen species of live, fruiting trees to keep metabolism fired up day and night, and in just a few hectares of nesting forest perhaps a 20-30 dead trees at just the right stage of rot — with just the right holes to shelter eggs and nestlings as a new quetzal generation takes form. It’s a specialized life.

Building on Skutch’s work were studies in Monteverde, Costa Rica, and Chiapas Mexico during the 1980s, 90s, and early 2000s. Details of these will emerge in the chapters that follow, but a few findings stand out, helping to complete our portrait of this bird. From Monteverde, we discover the intricacies of how fruits and quetzals have co-evolved: how Resplendent nesting is timed to take advantage of peak fruit availability; how those Lauraceae fruits, so crucial to quetzal life, can ebb and flow seasonally, and year to year; how in years when fruit is scarce the quetzals may delay nesting, or abandon it entirely; and perhaps most importantly, how quetzals help replant the forest, completing the cycle. A single quetzal, in just one month, can regurgitate the digested seeds of 100s of fruits. Multiply that by many quetzals over many months, and you start to see how much in debt these highland forests are to Resplendent Quetzals — as well as to many other animals that eat the same fruits. These are the forests, ecological powerhouses in their own complex ways, that turn sunshine into quetzals. Quetzals, it turns out, are helping to keep these same forests alive.

Seasonal shifts in the availability of fruit are common in quetzal highlands, with the most predictable declines at the end of the breeding season. As a result, hungry Resplendents tend to wander after nesting, after their young have taken wing. A key Monteverde study, using radio transmitters attached to dozens of Resplendent Quetzals to follow them over the year, found the birds moving to lower elevations in early fall, where fruit was more available, and then wandering on to other areas before returning to their traditional nesting sites in January and February. For conservationists, these findings had important implications: no longer could nesting forests be the only focus for protection; efforts were needed in “migration” areas as well.

From Chiapas, an excellent series of studies in the 1990s by Sofía Solórzano, Mexico’s premier quetzal biologist, helped confirm similar food preferences among northern Resplendents (their southern relatives in Costa Rica very likely a distinct species, Sofía’s data suggest), as well similar tendencies to move away from breeding grounds for half the year, when fruit became scarce. But perhaps most importantly her studies documented an alarming loss of cloud forest in that region; in just the three decades between 1970 and 2000 Chiapas lost almost 80% of the habitat Resplendent Quetzals depend on — cut, bulldozed, or thinned, mostly for coffee and cattle farms. Such loss was hardly restricted to Chiapas, although reliable data have been harder to come by elsewhere. But one thing was clear: by the early 2000s, and even more so today, this “king of the quetzals” was increasingly dependent on just a handful of large reserves, some of them better protected than others. That was the bad news. The good news was that many of these reserves were (and remain) very large, some of them hundreds of thousands of hectares, and quetzal populations appeared surprisingly robust in such habitat, with breeding numbers higher than earlier estimates had suggested. The challenge, of course, is keeping those forests intact enough to ensure that vibrant new generations of feathered quetzals emerge from dead trees every year. We’ll explore those challenges in the chapters ahead.

As we are beginning to learn, cloud forests have extraordinary value, biologically as well as economically, far more than the coffee and cattle that replace them. This montane, mist-soaked habitat supports some of the highest biodiversity on the planet; in Central America alone, where just 1-2% of its remaining land fits this category, more than 5% of plant and animal species would be lost if that highland forest belt disappeared. Just as important, these forests act as a giant sponge, soaking up water and releasing it slowly in sparkling streams and underground aquifers, a lifeline for farms and towns at lower elevations.

Water and quetzals. Both have a role to play in encouraging cloud forest preservation. Arguably, quetzals (at least Resplendent Quetzals) could take on a more prominent role — less easy to take for granted, as water often is, and more likely to spark the motivation needed to head off the formidable economic pressures that threaten montane forests in Latin America. I joke about Resplendents being the “million dollar bird,” but in reality they are all that and more. Viewing and photographing this quetzal is now a thriving business in parts of Central America — especially in that eco-tourist mecca, Costa Rica, but also in Guatemala, Panama, and Honduras. It could be much more. Lodges, guides, restaurants, busses, rental cars: it all adds up, and savvy conservation groups, especially in Costa Rica, now encourage local farmers to keep their land “quetzal-friendly,” with fruit and nesting trees preserved. In return, the farmers see a steady flow of tourist revenue for their efforts.

It’s difficult to over-emphasize the lure, the draw these birds still have. While you can measure the impact of some of this in tourist spending, for anyone who has glimpsed even one of these birds it is obvious there’s a whole lot more involved. Resplendent Quetzals have become the “flagship species” for cloud forest conservation in Central America because of something more ineffable than money. It’s what they do to us. That trailing “tail;” the splendid crest; the warbling calls drifting down from epiphyte-laden branches; the exuberance of courting males in flight on sunlit mornings; a lizard-delivering female at a nest hole, young feathered heads poking out to receive it. There’s an otherworldly aspect to this bird; something that takes us back to a time of Aztec chieftains, to a place where people and mountain wilderness were more in balance, to earth in its prelapsarian splendor. Splendor is a lot of what this bird is about, and in its presence we can’t help but feel lucky — to have evolved alongside a bird this splendid on a planet that still has room for us both. This book will explore that splendor, and what we can do to hang on to it.

—

The book was published October 15, 2023 by Comstock Publishing Associates.