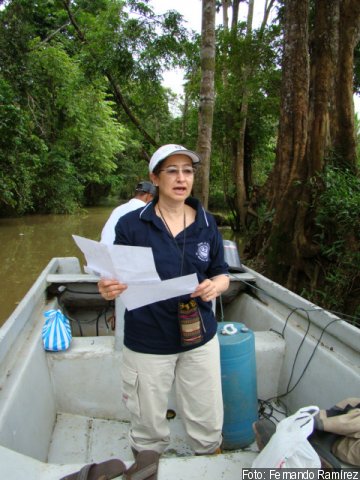

Luisa Castillo pioneers research on pesticides in Costa Rica

During graduate school in the 1980s, Luisa Castillo knew she wanted to be a scientist who studied the impact of pesticides on living creatures, an ecotoxicologist.

There was just one problem: she needed a laboratory. So, Castillo, solved this conundrum by creating a suitable laboratory for herself.

“It was the beginning of the 80s, and there were no ecotoxicologists yet in Costa Rica. The field was just starting out as a science, so I had to develop the laboratory,” she said. “It was hard work.”

She first secured an empty storage unit from her advisor. And then she began scouring peer-reviewed journals and ordering supplies to get it up and running.

This laboratory became a family affair for Castillo. On the weekends, she would sometimes bring her two young children to the laboratory. And her husband would occasionally accompany her on road trips to pick up supplies that could only be found on the coast.

This wouldn’t be the only laboratory or initiative that Castillo pioneered.

At the same time that she was studying for her master’s degree from the University of Costa Rica and her doctorate from Stockholm University in marine ecotoxicology, she developed the Pesticide Program and later the Central American Institute for Studies on Toxic Substances (IRET) at the National University of Costa Rica. This institute, which Castillo spearheaded, houses interdisciplinary scientists to engage in a combination of research efforts, postgraduate education and extension with the community.

Complementing her scientific expertise, Castillo has invested in engaging with policy and community education efforts throughout her career.

“The most meaningful part of my job is developing knowledge, providing this knowledge to the public – not only to scientists and not only in Costa Rica, but internationally,” Castillo says. “I value the international collaboration that we (IRET) have had throughout the years.”

“I think I never had any other idea in my mind but to study science. It was built into me.”

Tracing the Path of Pesticides

Castillo comes from a long line of scientists; she follows in the footsteps of both her great-grandfather and father who were both scientists.

In fact, her father’s training brought Castillo all over the world during her childhood. She was born in El Salvador, but lived in Switzerland and the United States (both New York City and San Francisco) before finding her way to Costa Rica with her family.

“I think I never had any other idea in my mind but to study science,” she says. “It was built into me.”

But scientists weren’t the sole group of people who inspired Castillo’s path.

While working at the University Nacional of Costa Rica, she says she was struck by her visits to farms where she spoke with community members and farm workers. She saw women and children in close proximity to dangerous pesticides. Farmworkers shared with her how shrimp and fish were suffering in nearby rivers that were exposed to pesticide runoff.

“It was easy to see that research was very much needed,” Castillo said. “While there was information from other countries, there was a need to generate our own information.”

Castillo decided to address this need head-on by using her newly built laboratory to focus on better understanding the impacts of pesticides on shrimp in Costa Rica for her M.Sc. dissertation.

As part of her doctoral studies, she also began to study the trajectory of pesticides outside of farms. For this research, she worked in the Pacific rice plantation area and the Caribbean

banana plantations. She used two OTS research sites: Palo Verde Research Station and La Selva Research Station. Palo Verde, which is surrounded by rice and sugar cane plantations, was a suitable spot for studying the trajectory of nearby pesticides being used on these farms, Castillo says.

In contrast, La Selva, back in the 1980s, was not surrounded by farms, which made it a suitable reference site for Castillo for her studies on the impact of banana plantations on Caribbean aquatic ecosystems.

These studies showed the presence of pesticides downstream of the agricultural areas, as far as the coastal lagoons in the Caribbean Coast, where they were affecting the flora and fauna along the way, she explained. Castillo describes that pesticides “disrupt the ecosystem” in the water by offsetting the species composition.

For example, certain pesticides, or the mixture of these chemicals, can affect macrobenthic organisms, fish, or spur the growth of toxic algae. These changes can then have a ripple effect on other organisms in the food chain.

La Selva is uniquely situated within an altitudinal gradient, with La Selva at 35 kilometers above sea level and Volcan Barba at 2,906 meters above sea level. This allowed Castillo and Canadian colleagues at a later date, to study the occurrence of pesticides from the mountains to the sea.

“We started finding pesticides not only where you expected them in the surroundings of the banana plantations, rice farms, and pineapple farms, but we started finding these pesticides all over, including downwind of the agricultural areas” Castillo says.

The pesticides, which are in liquid form, can convert to a gas through a process called volatilization. These volatilized pesticides traveled via wind to the mountains. Once temperatures lower, these pesticides return to land via “rain or fog,” Castillo says.

“The impact of these pesticides in the mountains has not really been studied,” Castillo says. “But what we can say, and that’s already important, is that there are substances present that don’t exist naturally in the mountains. They shouldn’t be there, but they are.”

Castillo has recently received funding from OTS to recover all pesticide residue data from different project carried out (1992-2011) in the surroundings of the Palo Verde area, prepare an integrated data base and carryout a trend analysis of the results. A proposal to continue efforts to monitor the path of pesticides and microplastic is being prepared. “This work would give us a better picture of what’s happened there in the last 30 years,” Castillo says.

“The most meaningful part of my job is developing knowledge, providing this knowledge to the public – not only to scientists and not only in Costa Rica, but internationally”

Engaging Diverse Stakeholders

Castillo may have been one of the first ecotoxicologists in Costa Rica, but she won’t be the last –thanks to the efforts of Castillo and colleagues at IRET. “At the beginning, it was just me,” Castillo says with a laugh. “But by the time I retired, there were 40 people working at the institute and we had developed two master’s degree programs”, one in Occupational Health and the Tropical Ecotoxicology Master Program.

One of her goals with IRET was to foster international and interdisciplinary research. Within the institute, Castillo says there is a varied group of scientists, including “chemists, biologists, agronomists, health persons, and epidemiologists.”“Pesticides, or toxic substances, affect basically everything, so you need to gather a set of people to see what happens, how to solve it, and how to propose to change it,” she says.

Figuring out how to initiate “change” related to pesticide use is a topic Castillo has invested in throughout her career. Specifically, she has promoted work with the government and other institutions on policy-related matters to try and address solutions in an applied way.

For example, IRET has a close working relationship with the Ministry of Environment. Castillo says their team has helped out with analyses, as well as training people through master’s programs at IRET. When the Ministry of Environment has questions related to ecotoxicology, they have historically reached out to IRET.

Currently Castillo channels her insight collaborating with policy leaders through her close involvement with OTS’ Decision Makers Course. Through these courses, decision makers – from elected officials to NGO leaders – come together in Costa Rica to learn about environmental policy, with topics ranging from forest ecology to ecosystem services.

And this isn’t Castillo’s only involvement with OTS. In addition to her research efforts and engagement with the OTS’ Decision Makers Course, she also invested in education efforts in the 1980s. Specifically, she helped train primary and high school teachers in environmental science, and OTS hosted many of these courses.

Castillo also actively works to disseminate research findings back to the community. She views these community members as integral to the scientific process.

About the author

Rachel Damiani is a freelance science writer and the founder of Ecotone Science Writing & Photography, LLC. She received her Ph.D. in communication, M.A. in mass communication with a concentration in science/health, and B.S. in biology from the University of Florida. Prior to opening her business, Rachel worked as a science communications specialist for a large university and a research assistant in multiple biology laboratories. Her sole and co-authored work has been published in a variety of outlets, from the Washington Post to Ecology. As a freelance science writer with the Organization for Tropical Studies, Rachel enjoys collaborating with OTS staff, interviewing scientists and students from around the world, and telling stories about their fascinating research.