Venturing into the unknown: Cathy Pringle carves a career in the science of streams

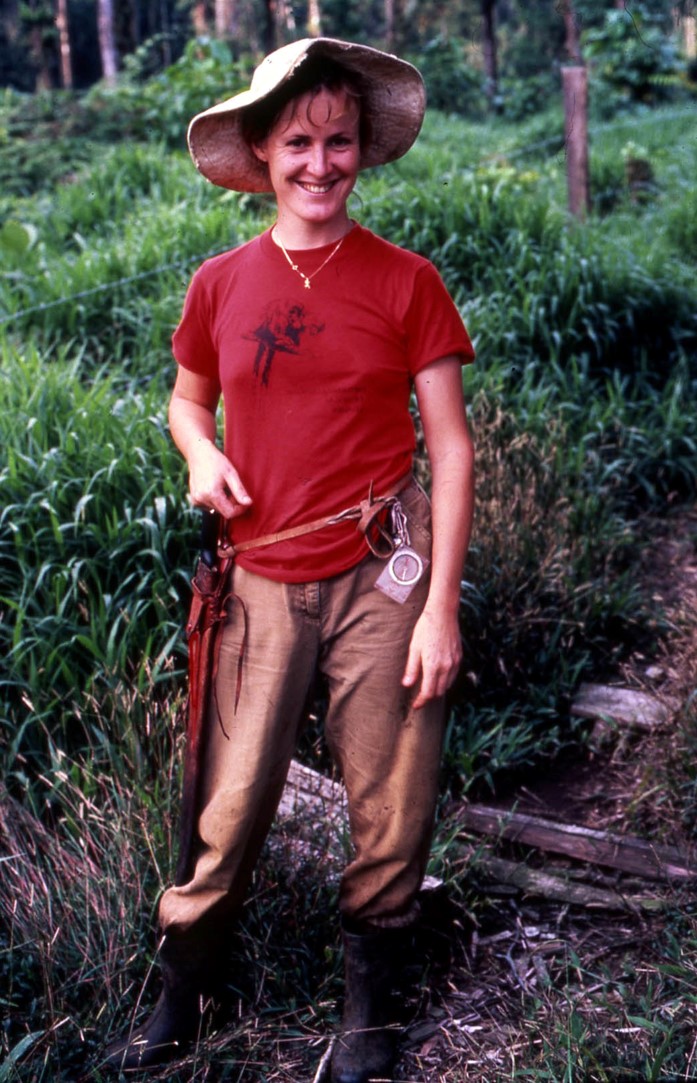

Catherine Pringle, now a distinguished research professor, was once a 28-year-old graduate student spearheading a group of scientists on an expedition into the rugged land connecting La Selva Research Station to Braulio Carrillo National Park.

It sounds straight out of a blockbuster movie plot, rather than the real-life, adventurous start to Pringle’s illustrious career as a tropical ecologist.

This expedition would lead to the discovery of multiple new species, a symposium at the California Academy of Sciences, a co-edited book focusing on the findings of this expedition (Almeda and Pringle 1988), postage stamps, and the eventual incorporation of this corridor into Braulio Carrillo National Park.

“The expedition opened my eyes to the incredible plant and animal diversity on the forested slopes above La Selva and helped me better understand the rivers and streams and hydrology of La Selva from a broader landscape context,” Pringle said.

After this first trek in 1983, Pringle received her doctorate from the University of Michigan and spent three years as a postdoctoral associate at the University of California, Berkeley and Santa Barbara. Today, Pringle produces cutting-edge research on stream ecology at the University of Georgia’s Odum School of Ecology – a research focus she cultivated through decades of field work at La Selva, Costa Rica and projects in Puerto Rico, Panama, Trinidad, Georgia, and North Carolina. She is also past President of the Society for Freshwater Science, and a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Ecological Society of America.

But let’s start back at the beginning of this story in 1982, when Pringle was a student in her first OTS course at La Selva. She heard a lecture from Dr. Deborah Clark, who was co-director of La Selva at the time, that piqued her interest.

An intrepid undertaking into the unknown

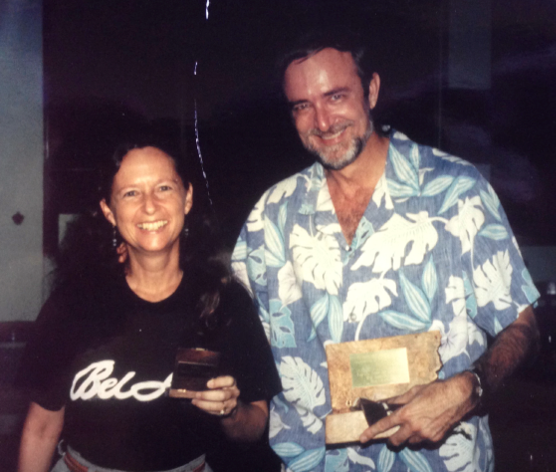

Deborah and David Clark, former Co-Directors of La Selva

Pringle listened attentively to Clark as she gave her “Introduction to La Selva” lecture.

Years from now, many of the students sitting next to Pringle would become well-respected scientists in their own right, including Sally Horn, Professor of Geography at the University of Tennessee, Lynn Gillespie, Director, Canadian Museum of Nature, and Drew Barton, Professor of Biology at the University of Maine.

For now, these scientists-in-training digested Clark’s lecture and learned that La Selva was “an island surrounded by cow pastures on three sides,” according to Pringle. The fourth side was something completely different – unsettled land that linked the station to Braulio Carrillo National Park.

“Deborah explained that, if the forested land corridor could be protected, it would connect La Selva to this large montane park,” Pringle said. “She is an incredible speaker, an amazing scientist, and her enthusiasm got me excited about it.”

There was momentum to protect this “corridor.” In April 1982, a presidential decree had named this land a Zona Protectora, meaning a protection zone.

The “La Selva Protection Zone” was remarkable in that it linked two distinctly different environments. La Selva (35 m) is in lowland wet forest, while the summit of Volcan Barva (2,906 m) in Braulio Carrillo National Park is in montane cloud forest.

This altitudinal transect, which is the last forested one of its kind spanning such extremes in elevation on the Caribbean slope of Central America, had the potential to serve as an important passageway or corridor for multiple creatures, including migrating birds.

“The expedition opened my eyes to the incredible plant and animal diversity on the forested slopes above La Selva and helped me better understand the rivers and streams and hydrology […] from a broader landscape context”

Despite the possibilities, much remained unknown about what organisms thrived in the La Selva Protection Zone. Pringle finished the OTS course in 1982 and then decided to channel some of her enthusiasm into action by applying for post-course funding to explore the corridor.

“I had met Don Stone, who was the executive director of OTS at the time, and we got to talking about the possibility of having an expedition into the area,” Pringle said. “I wrote a post-course grant to get money to organize an expedition, and OTS funded it.”

After receiving the OTS Noyes grant, the hard work began, and this was work without a clear road map. With recommendations from Stone, Pringle began to bring together a group of scientists to join her on the expedition.

Indeed, this was quite an impressive list of scientists.

The scientists included Gary Stiles, a well-known bird expert at the Universidad de Costa Rica, Harry Green, a herpetologist at the University of California, Berkeley, two botanists, Michael Grayum from the Missouri Botanical Garden and George Schatz then from the University of Wisconsin, Isidro Chacon, an entomologist at the time operating from the Museo Nacional de Costa Rica, Carlos Gomez, an entomologist from the Universidad de Costa Rica, and Gary Hartshorn, a forester from the Tropical Science Center of Costa Rica.

Pringle, a new doctoral student, began contacting these seasoned tropical scientists.

“I’d call them up, and they’d ask, ‘Well, who are you?’” Pringle said. “And I said, ‘Well, I was told that you’d be the perfect person to come on this expedition. Will you join us?’”

While some scientists may have been skeptical at first to receive an invitation for an on-foot expedition by a graduate student, they said yes. So, in January 1983 they embarked on a two-week journey. In the one photograph of the full crew, Pringle, the only woman on the expedition, kneels in the front row.

For this first 1983 expedition —yes, there would be more expeditions down the road — the scientists and their gear were transported by tractor via muddy roads through Tirimbina to the lower elevations of the land corridor near La Selva’s back boundary. It was here where the scientists were deposited, along with their backpacks, tents, and freeze-dried food.

The scientists set out on foot from their base camp as a storm descended upon them. Pringle said this rain would be constant throughout their trip.

Their goal? Figure out what was present in the La Selva Protection Zone. One of Pringle’s earliest memories of the trip was coming upon a waterfall close to their base camp.

“I’ll just never forget coming upon it thinking, ‘I can’t believe I’m just upstream of La Selva.”

“You hiked up this river and then, around a bend, there was this incredible waterfall,” Pringle said. “I’ll just never forget coming upon it thinking, ‘I can’t believe I’m just upstream of La Selva.’”

This waterfall was just the first of many discoveries in the corridor. Pringle watched as Schatz and Graham recorded and collected plant species, including 28 newly discovered ones, throughout the expedition.

“I remember Schatz and Graham collecting plants, bringing them back, and pressing them in their tents away from the drizzling rain with newspapers,” Pringle said.

She also watched Stiles, the ornithologist, as he observed birds and collected and prepared some specimens for the museum. Styles reported that “at least 35 bird species use these forests for altitudinal migrations,” according to the peer-reviewed paper presenting the expedition findings in Brenesia.

This land corridor was bustling with more than birds and plants. Chacon and Gomez observed more than 175 species of butterflies, and Green reported 18 species of mammals and 17 species of frogs and toads. Some of the frog species observed on the expedition (e.g., Atelopus varius) have since been extirpated from the area due to a chytrid fungal pathogen that decimated many stream-dwelling frogs in the decade following the expedition.

The 2,870-meter altitudinal gradient that was only about 35 km in length was 73% primary forest, 6% young secondary growth, and 3% secondary forest.

Armed with insight into both the ecological life zones in the corridor and the creatures occupying it, the scientists had a convincing case for future expeditions and conservation of this unique stretch of land.

A few years later, scientists embarked on another expedition “Operation Raleigh.” This expedition was led by Gary Hartshorn and Rebecca Butterfield and was funded by the National Geographic Society.

Pringle joined this expedition along with her colleague, Frank Triska, who was a hydrologist and freshwater ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, CA. The scientists explored higher elevations of the land corridor and into the Braulio Carrillo National Park.

In 1986, Luis Alberto Monge (President of Costa Rica 1982-1986) signed a decree incorporating this corridor land into Braulio Carrillo National Park.

Pringle documented her experience during this expedition – and her involvement with OTS in fundraising to obtain the corridor land – in a co-edited book with Dr. Frank Almeda, an emeritus botanist at the California Academy of Sciences.

Carving out a career in stream ecology at La Selva

At 29 years old, Pringle may have already organized a game-changing expedition into the La Selva Protection Zone with trickle-down impacts for years to come, but she still had a doctorate degree to complete.

Luckily, Pringle knew what she wanted to study during graduate school: stream ecology.

Pringle, who was born and raised in Michigan, said she grew up “playing in the creek and observing tadpoles.” When she first visited La Selva, she was struck by the abundance of water.

“La Selva receives 4-5 meters of rain per year and is bisected by a multitude of streams,” she said. “As a stream ecologist, I was intrigued and captivated with the idea of working there.”

This fascination led to long-term field work at La Selva. For her postdoctoral work at La Selva, Pringle expanded her post-OTS course research on stream chemistry. She noticed something unexpected: some of the streams had a high concentration of dissolved substances (e.g., solute-rich). These streams had a high concentration of phosphorus, bicarbonate, chloride, and a host of other elements. In contrast, other adjacent streams had low levels of these substances (e.g., solute poor).

“I’d learned that many neotropical streams were low in nutrients, and here we were finding high levels of phosphorus, the levels you might find below a sewage treatment plant,” Pringle said.

It wasn’t until Pringle stumbled upon an obscure reference in a paper that she began to wonder if the stream chemistry at La Selva might be impacted by underlying geothermal activity. This helpful paper was written by volcanologists studying nearby Poas volcano, which was located in the mountains just “one volcano northwest” of Volcan Barva in Braulio Carrillo National Park.

“You tend to forget, when you’re in the lowlands of La Selva under the dense canopy, that you’re at the base of a dormant volcano,” Pringle said. “While the volcano is not visibly active, there is hot magma deep underneath.”

Belowground, the volcanic magma produces a gas, hydrogen sulfide. This gas rises and is absorbed in subsurface water, Pringle explained. This acid sulfate groundwater then flows downslope over 30 km, cooling and weathering rocks. This weathering process causes bicarbonate, phosphorus, and other elements to leach from the rocks and feed into some streams at La Selva.

It’s this process, which connects the volcano to streams, that can result in high-solute streams at La Selva and provides an explanation for the anomalies in stream chemistry that Pringle had previously documented.

Pringle has continued to build upon these initial findings and study the streams of La Selva for the past 40 years. Since the 1980s, Pringle has mentored 52 graduate students and co-authored over 200 peer-reviewed papers and 47 book chapters and symposia.

During her postdoctoral work, Pringle received funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to begin the STREAMS project – a project that has been continuously funded by the NSF since 1988. Her collaborators include Triska, who became Pringle’s co-investigator on the first four cycles of NSF funding, as well as two of her former doctoral students, Dr. Alonso Ramírez and Dr. Marcelo Ardón, who are both faculty at NC State University.

Initial research through the STREAMS project focused on better understanding ground and surface water chemistry at La Selva and adjacent areas and how it was affected by underlying geothermal activity associated with the volcanic mountains. This work led to the STREAMS Project’s focus on understanding how phosphorus impacted stream ecosystem processes (including algal growth, decomposition, and food web dynamics) and ultimately (in the 2000s) on stream resistance and resilience to climate change and variability.

From the science of streams to exploring the unknown, Pringle described the catalyzing role of OTS in her career. She said she was emboldened by a variety of “strong and talented women,” including Jean Stout, Robin Chazdon, Deborah Clark, Deedra McClearn, Gail Hewson, Bette Loiselle, Beth Braker, Pia Paaby, Julie Denslow, Nalini Nadkarni, Pat Wright, Katherine Ewel, and Karen Lips.

“Their leadership and commitment to tropical science were an inspiration and led to many close friendships and even future collaborations at other tropical locations, including research in Madagascar with Pat Wright, Micronesia with Katherine Ewel, and Panama with Karen Lips,” she said.

It’s not only the people she met, Pringle says, but the opportunities that OTS as an organization provided her that have been foundational to her career.

“OTS changed my life and launched me into working in all of these tropical places. The organization gives women the chance to really flourish, […] OTS has similarly served as a springboard to career opportunities in tropical ecology and conservation for hundreds of young people, affecting the trajectory of their lives and contributing to science and conservation.”

About the author

Rachel Damiani is a freelance science writer and the founder of Ecotone Science Writing & Photography, LLC. She received her Ph.D. in communication, M.A. in mass communication with a concentration in science/health, and B.S. in biology from the University of Florida. Prior to opening her business, Rachel worked as a science communications specialist for a large university and a research assistant in multiple biology laboratories. Her sole and co-authored work has been published in a variety of outlets, from the Washington Post to Ecology. As a freelance science writer with the Organization for Tropical Studies, Rachel enjoys collaborating with OTS staff, interviewing scientists and students from around the world, and telling stories about their fascinating research.